The humble yet magnificent hippopotamus deserves major acknowledgment. A big-ticket item in any safari trip or park visit, these salad-loving powerhouses are truly iconic. Such settings are the only places that many have ever seen hippos. But the United States could have been much more familiar with them. In fact, the country could have earned recognition for its hippo ranchers!

Meet The Potential Solution To The Meat Problem

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the United States was in the grip of two potentially devastating issues. The first, a food crisis brought about by a lack of access to meat. According to Portland State University’s Catherine McNeur, meat providers across the nation were accused by the people of “conspiring to profit at their expense.” During the same period, an elaborate plant, the water hyacinth, had relentlessly spread across the south after being introduced at the 1884 Cotton States Exposition. It grew faster than anyone could remove it, clogging up the waters in the process!

The United States entered the twentieth century with some unique dilemmas to resolve. However, one particularly large and meaty plant-eater comes to mind to devour those troublesome hyacinths. The curious thing is that hippos actually eat surprisingly little: Their daily (or rather nightly) diet of around 88 lbs of food is relatively modest for such a hefty creature: The largest male hippos can weigh almost 10,000 lbs!

We don’t know if they would be particularly effective at devouring those plants. One thing however that’s difficult to deny is that a hippo has a tremendous amount of flesh. For these reasons, it seems, a United States-wide network of hippo ranches almost became a reality.

The very concept sounds outlandish, but there’s a strange kind of logic to it. As Jon Mooallem explained to WIRED, “The idea was that you could harness land that wasn’t productive for grazing cattle, like swamps and bayous. So you’d transplant the hippos into these environments that aren’t totally unlike where they live in Africa.” But how would the hippos have made it to the United States, and what was the plan for them from there?

Mass hippo importation from the creatures’ home continent was the plan.

The Hippo Bill

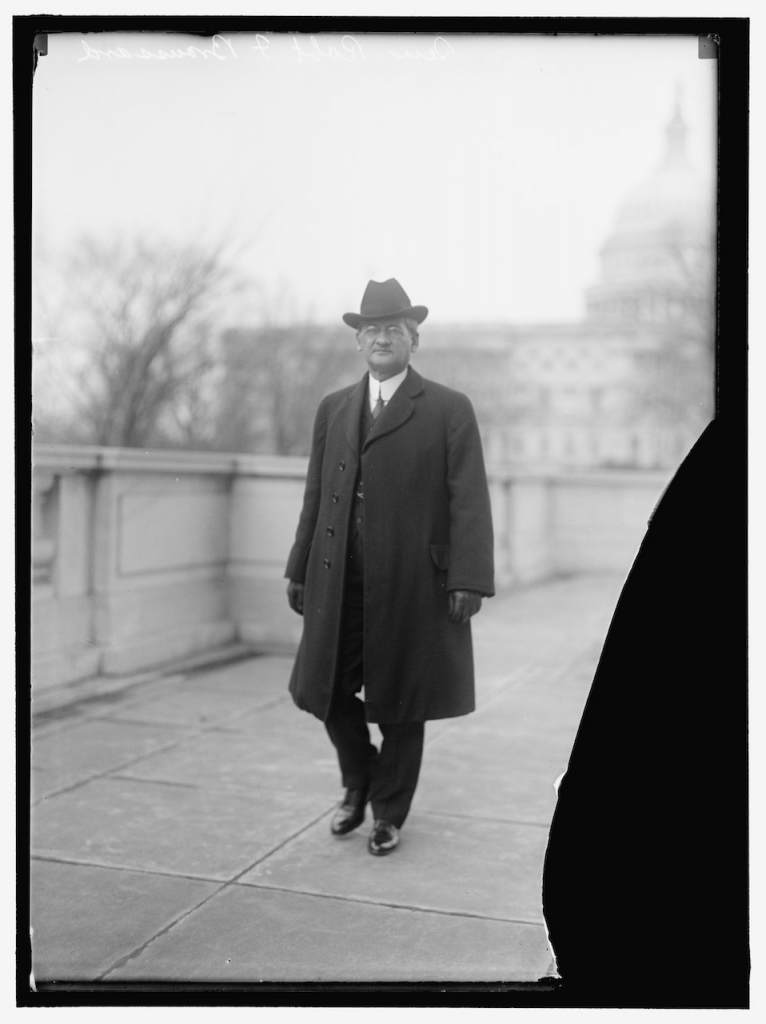

House Resolution 23261, more commonly known as the American Hippo Bill. The bill was brought to the House Committee on Agriculture in March of 1910. Advocating for it was Louisiana’s own Robert F. Broussard.

The title of the bill does not address the magnificent hippopotamus directly. Rather the wider issue of importing animals, both domestic and wild, into the United States. During the meeting, W.N. Irwin of the Department of Agriculture’s had some choice words. Irwin’s statement notes that “it seems rather strange that for four hundred years we have continued to use three animals for our meat supply – cattle, sheep, and swine.” For any nervous hippos reading this, yes, you can probably see where this is going, and you’re not going to like it.

Robert F. Broussard. Credit: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Irwin went on to note that these were species imported from Europe, and that the price of meat had risen to such a degree that it wasn’t conceivable to meet the increased demand and ensure the people were fed. Irwin’s proposed solution to this issue? “… we get the hippopotamus here – an animal whose flesh is excellent in quality and that is easily kept in suitable locations.”

The vast land of the United States, as Mooallem reported, offers such locations, which would be entirely impractical for ranches for other species. Irwin even suggests the rhinoceros as another possible ranching candidate, as he claims the desert regions of the United States, harsh areas where few other species can thrive, would be suited to their needs.

Irwin went on to claim of the hippopotami that “the people who have handled them tell me they are very easily tamed, and become very much attached to man.” He did note that they had a tendency to travel far (15 miles overnight). According to him, though, fencing would allow them to be easily controlled. All in all, it seemed, the case was made. So-called “lake cow bacon” could have become as commonly consumed as … well, bacon.

The Flaws And Fate Of The Hippo Plan

Ultimately, though, the hippo-ranching dream would not become reality. A combination of factors would see the controversial bill fail to take off. There were a few dramatic holes in the logic. For one, Hippos and water hyacinths don’t totally mix. While they do consume plants that grow on the water, their preference is for grasses, and they can spend about five hours every day grazing on just that.

While we didn’t ultimately get to see exactly how this would happen, it seems clear that the hippos would have been unwilling to help much with the hyancinth problem. It’s very likely that the huge creatures would have proven far less pliant than Irwin boldly claimed they would. As long-roamers, it is unlikely that keeping large groups of them enclosed would have been a practical task.

Pontederia crassipes known as the common water hyacinth. Credit: Shutterstock.

Nonetheless, there was some press support for the plan. A piece in the contemporary Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, according to Mooallem in Atavist, dreamed of “that golden future when the meadows and the bayous of our Southern lands shall swarm with herds of hippopotami.”

How It All Played Out

Political disagreements ultimately doomed the idea: Congress’s break was approaching, and the proponents of the New Food Society, struggled to collaborate to concentrate their efforts.

Amidst these troubles, the emergence of World War I and the global devastation it caused meant that other priorities would ultimately see the efforts fizzle out. The Hippo Bill remains one of the most peculiar “what ifs” in American history.

By Chris Littlechild, contributor for Ripleys.com