Humankind has envied birds and other flying animals for millennia. The sheer exhilaration, the freedom, the ability to eschew busy airports and pricey flights… wings certainly are quite the evolutionary boon! There’s a reason why one of the most-ballyhooed superpowers displayed in comic books and other media is flight.

In Scott Lobdell and Pascal Alixe’s “Red Hood and the Outlaws #14,” per CBR, Superman takes just seconds to fly from the distant Pluto to the Earth he so loves. Considering that the distance between the two is 2.66 billion miles (4.28 billion km) at the furthest point of their orbit, it’s clear that this is infinitely far beyond anything that’s even remotely realistic. That’s part of the fantastical appeal of flight, though.

For the first bold pioneers of aviation, vehicles that could actually carry us into the air may have seemed equally impossible. Through their perseverance and ingenuity, though, some of the furthest reaches of the globe are accessible. We can enjoy travel on a scale that would have seemed far beyond our reach just a century ago.

Who do we have to thank for this? For many, the Wright Brothers are considered the true pioneers of flight. The truth is, however, the successful siblings actually weren’t the first humans to achieve flight!

The Wright Brothers Take Off

Wilbur and Orville Wright were born in April 1867 and August 1871 respectively, the sons of Church of the United Brethren in Christ minister Milton Wright. The brothers’ creative flair was first evident in the printing presses they developed together, but they set their sights on even loftier ambitions.

According to one brilliant story, the brothers’ ground-breaking work in the field of aviation was partially inspired by a simple toy their father had gifted them when they were boys. It was, per History, a simple paper and bamboo helicopter, “powered” by means of a rubber band. Seemingly inconsequential as the gift may have been, it reportedly sparked something in their young minds: an interest in flying machines and a drive to create their own.

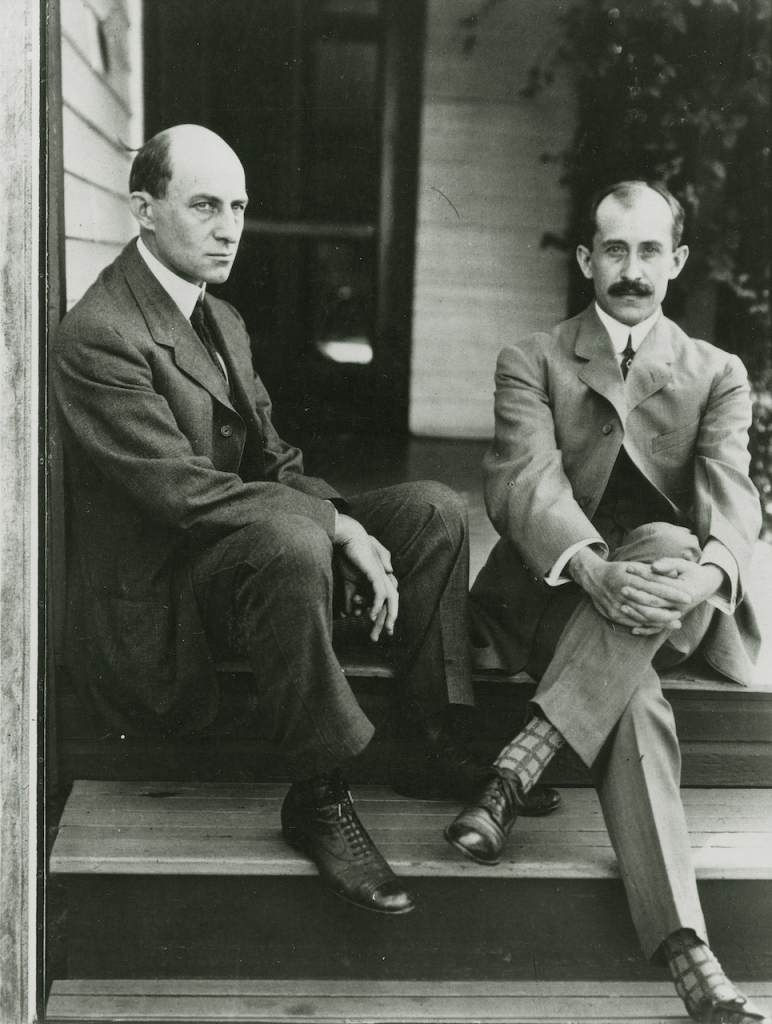

Wilbur, left, and Orville Wright sit on the porch steps of their Dayton, Ohio, home in June 1909. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The outlet goes on to explain that the little helicopter had been inspired by Alphonse Pénaud, who himself was dreaming up flying machines over in France. The year was 1878, incredibly early in the history of aviation, but one thing was absolutely certain from this little story: the concept of flight did not begin with the legendary sibling duo. Not by a very long shot. They were not the first to achieve flight, either.

The Legendary Siblings’ Achievements

The Wright Brothers’ story is certainly the most iconic and popular, though, when it comes to the topic. Their work faced all manner of challenges, but the technically and mechanically gifted brothers found ways to overcome them.

How, they wondered, to design wings that could successfully both get and stay aloft? They found the answer to this in nature: Emulate the angles at which birds hold their wings. It wasn’t until December of 1903 that one of their designs could achieve flight, and very brief flight it was: 59 seconds with Wilbur at the helm. History defines this achievement very specifically: “the first free, controlled flight of a power-driven, heavier-than-air plane.”

When considering who flew first, it’s a very important distinction. The Wrights, the outlet went on, were certainly at the forefront of aviation. Their success, then, was limited (particularly at first) by those who didn’t trust these newfangled flying machines, or perhaps didn’t see them as very practical. Much more would be needed than a demonstration of less than a minute, after all.

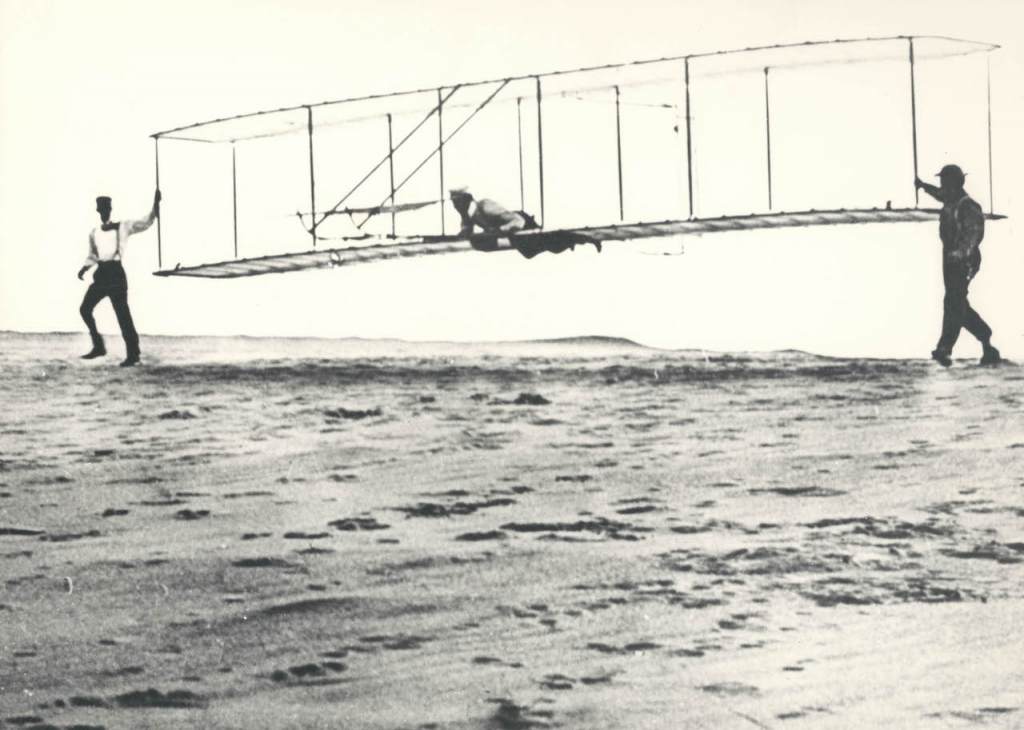

Historic photo of the Wright brothers’ third test glider being launched at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, on October 10, 1902. Credit: NASA on The Commons Via Wikimedia Commons.

Per NASA, the pioneering pair weren’t able to successfully take off and land back in the same location until September of 1904, in a new model of their Wright Flyer. The journey was 1 minute and 36 seconds long, which was still, while a remarkable engineering feat, far from any practical use in a wider sense. It was only the following year, with the Wright 1905 Flyer, that they succeeded in achieving sustained flight of more than a half-hour.

From there, the siblings firmly established their place in aviation history. As the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum reports, their pioneering efforts resolved some of the major conundrums that would-be pilots faced. The concept of “wing-warping” was their true masterstroke. By developing a way of adjusting the angles of the wings, they avoided the problem of lift having an uneven effect on both wings, and so on the craft itself. Sustained and stable flight of a motor-powered airplane that was heavier than air, then, was indeed first achieved by the Wright brothers.

However, there were those who flew before them, and to whom they owe a tremendous debt. Creativity breeds creativity, after all, and the brothers may never have achieved what they did without the aviation geniuses who came before them.

Earlier Flight Pioneers

One such person was the German Otto Lilienthal. Born in 1848, Lilienthal’s work was a huge influence on the Wright brothers. His Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst (“Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation”), published in 1889, tackled a subject that became central to the brothers’ work: the wings and how they should be adapted.

Like the Wrights, Lilienthal was an adept mechanic. A combatant in the Franco-German war, he used his expertise to develop a flight school and tackle that very same question of how to achieve flight and what to do with the wings.

Lilienthal’s flying machines were not airplanes, but gliders. He developed around 16 of them that he personally flew over 2,000 times, tweaking and altering his brilliant designs along the way. The standard glider he created was a glorious device, complete with a tail and multi-sectioned wings which were described as being based on “the outspread pinions of a soaring bird.”

The glider, however, was a fragile confection of wood and cotton, and left its pilot incredibly vulnerable. Sadly, Lilienthal proved this himself in August of 1896, when it failed him. He died the day after from injuries sustained during a crash.

Lilienthal was, however, flying in the century before the Wright brothers did. Much further back still, the early 1500s, the legendary Leonardo Da Vinci published a study similar to Lilienthal’s. It was called Codex on the Flight of Birds, and, yet again, explored the ways in the which the wings of birds and principles behind them could be adapted to create flying machines for humans. He famously drew up a design for a flying machine, but it was never built.

Balloon Animals and Other Feats of Flight

In September of 1783, History goes on, Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier and brother Joseph-Michel sent a curious trio of animals (a sheep, rooster, and duck) on a brief expedition into the sky in one of their marvelous balloons. Later that year, two humans followed on a half-hour flight.

Nicholas Louis Robert and Jacques Alexander Charles followed just days after, in a brilliant hydrogen balloon of their own. This flight was around four times longer than that of the Montgolfiers, and firmly established 1783 as the year that people first took to the skies in powered hot-air balloons.

“Ascension de Charles et Robert, aux Tuileries, le 1er décembre 1783.”

Were these, then, the first true flights? It depends how you define the term, really, but it’s absolutely certain, again, that the Wright Brothers weren’t the first to take to the air.

Not First, but Lasting Nonetheless

Their innovation was crucial is so many ways; to the United States Army for instance. The Wrights’ Flyer was contracted to the military to the tune of $30,000 (at the time) after achieving a 45 mph romp at Fort Myer in July of 1909. The army was thus in a great position to created advanced aircraft for use during the looming World War I.

Their technology, and the constant refinements it would go through at their hands and those of others, saw aviation advance at a speed that was truly remarkable. In June 1919, a little over six months after the end of the conflict, history’s first transatlantic flight was made (not by Charles Lindbergh, by the way).

The aviators who took this once-unimaginable journey were two Brits who served in the armed forces, Captain Sir John Alcock and Lieutenant Sir Arthur Whitten Brown. The iconic duo made the trip in a Vickers Vimy, a newly-developed bomber that had opened up the possibility of longer flights with its ample fuel storage. The flight from St John’s, Newfoundland, to County Galway, Ireland, took 16 hours and 28 minutes in total.

Wilbur Wright, who had died in 1912, did not live to see this aviation milestone. Though neither he nor his brother (who lived on until 1948) made this particular ground-breaking trip, their earlier efforts, and those who came before them in turn, certainly laid the foundation for it to happen.

By Chris Littlechild, contributor for Ripleys.com

I’m glad you made it clear that the Wright brothers were the first to fly in a practical airplane, but there are many others who should be known for their contributions, such as machinist Charles Taylor, who built the engines they designed. There was Sir George Cayley who experimented with a glider that had the basic layout of most modern aircraft and lifted off the ground with a human, Louis Pierre Mouillard who made observations of birds and wrote an inspirational book, “The Empire of the Air” (English translation), and Octave Chanute, who wrote the English translation, was a pioneer in gliding flight himself, and sponsored and encouraged many others, including the Wrights. There were a number of others who managed to get into the air for short gliding flights, Clement Ader and Alberto Santos-Dumont built powered machines that got off the ground, although as this article explains, there’s good reason the Wrights are rightly credited with being “first in flight” in the sense of inventing a fully working airplane.

See the “To Fly Is Everything” website: https://invention.psychology.msstate.edu